Edward R. Miller

Edward R. Miller

IN THE REGION | Long Island

By MARCELLE S. FISCHLER

Published: January 7, 2010

When Ms. Bard showed the renderings to her boyfriend, Christopher D. Bodkin, the chairman of Islip’s Community Development Agency and until recently a town councilman, she wondered why the cottages couldn’t be the model for “highly affordable, flood-resistant housing for those of us who live here.”

As opposed to public-assistance housing on the Island, which often has a larger footprint, “a tiny house is so much cheaper to live in,” she said.

Mr. Bodkin agreed.

“They are really charming,” he said of the Katrina models, explaining that he had reared two sons, now 27 and 29, in a 625-square-foot circa 1784 cottage with two bedrooms and a little attic in Sayville — and that the elder one still lived there.

The size was always perfectly adequate, Mr. Bodkin said.

At the next board meeting of the Community Development Agency, he passed around the catalog. When he asked why the town didn’t build similar homes, he “expected 10 hands to go up,” so that colleagues could air their objections. Instead, Gene Murphy, the town’s commissioner of planning and development, enthusiastically endorsed the idea.

“Besides its affordability,” Mr. Murphy said recently, “it’s a smaller house and it fits into the community. It is meant as good starter housing to get people out of basements. For what they pay for rent, they can build equity in a house.” Paul Fink, the executive director of the Community Development Agency, said he hoped that eventually 10 Katrina cottages a year could be built to complement the 30 to 40 larger affordable homes that the town erects.

The basic Craftsman-style cottage is 918 square feet, with two bedrooms and one bath. At 26 feet wide and 38 feet deep not including a front porch, it fits undersized lots, like those in older neighborhoods like Sunnybrook in Bay Shore, where the plot for the first planned house is located. Some vacant lots there are 50 by 100 feet. The current zoning minimum is 75 by 100.

“You can still keep decent side yards,” Mr. Murphy said, adding that the compact cottages wouldn’t “impact privacy of neighbors” or “overbuild the site.”

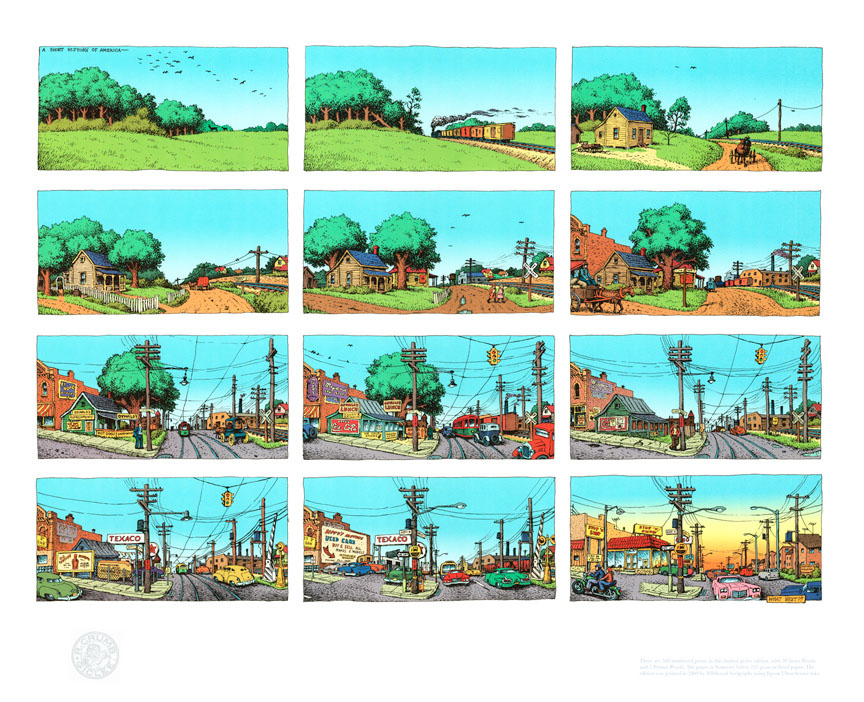

Also, the old-fashioned architectural style “fits in with the context of that neighborhood,” he said, which has housing stock built between 1890 and 1920.

Habitat for Humanity of Suffolk County, which received the property last year from the town and has applied for a building variance from Islip’s Board of Appeals, plans to start work on the first Katrina cottage in March, and do three to four more in town by the end of the year. Each cottage will cost about $100,000 to build, using volunteer labor.

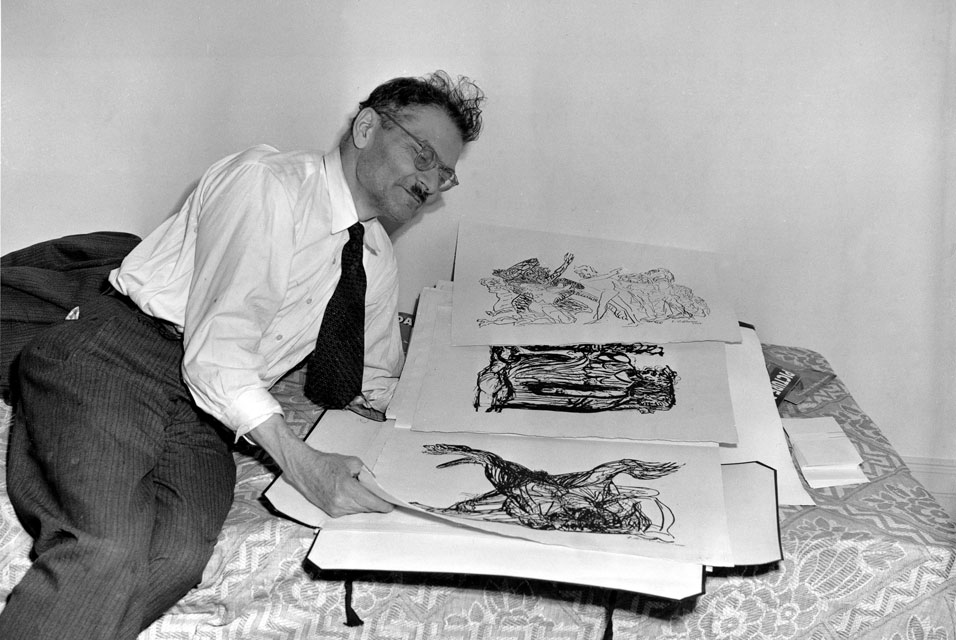

Ed Miller, the architect for Habitat, said that although he and his colleagues had used the Lowe’s catalog renderings as design inspiration, the plans for the Craftsman-style dwelling were their own.

“The house is small,” he said, “but it has nice curb appeal, a nice big porch that a family can sit on, going back to the old days when you could sit on the front porch and talk to your neighbors.”

Ornamentation will be different in each case, “to give each house its own unique look.”

Habitat will select a buyer by lottery, from an applicant pool of families making no more than 50 percent of the area median — $40,700 for a family of two. The layout is simple: toward the front, a small foyer with a closet, a living room and an eat-in kitchen; to the back, down a hallway, two bedrooms. The laundry room is in a closet area off the kitchen; the hall bath is wheelchair-accessible. The house is not air-conditioned and has no basement.

Mr. Fink of the Community Development Agency said that the first home would also have solar panels, low-maintenance vinyl siding and Energy Star appliances. Its compact size will help keep utility costs down. “We think this will wind up being less expensive than rent for many of the people who buy the houses,” he said.

Generally the affordable housing built by nonprofits in Islip — 1,100 to 1,200 over the last 30 years, mostly ranches and colonials — runs 1,200 square feet and has three bedrooms and one and a half baths. Comparatively, the original Levittown house was 750 square feet plus an expandable dormer upstairs.

With the 918-foot model, Mr. Fink said, “we are trying to meet the needs of other family sizes. We have single parents, we have single individuals who want to own their own home but a three-bedroom is a little silly.”

“If we look at who is applying to our lotteries,” he added, “we have more and more smaller families over the last few years. We have far more single parents and far more single individuals looking to buy a house.”

Diana Weir, the executive vice president of the Long Island Housing Partnership, which has built 50 to 100 affordable homes in the last two years, said the Katrina cottages were a lot smaller and more moderately priced than the 1,300-square-foot homes that the partnership usually builds, which range in price from $140,000 to $245,000 depending on federal and state subsidies.

The smaller houses are a “great alternative,” she said.